Solomonic judgments

Monday | May 7, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

The Great Blondin, from American Falls.

DB here:

Before you read any further, please go here and look and listen. Click on a few of the sample clips, such as Still Raining, Still Dreaming and Rehearsals for Retirement. Now try the extracts from American Falls here.

Take your time; I’ll wait.

Back? Good.

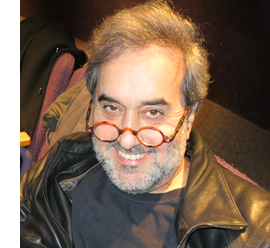

These excerpts can give you the flavor of Phil Solomon’s extraordinary filmmaking better than any prose of mine could. Solomon has been a major figure in the American avant-garde for nearly thirty years. I’m no expert on his work, but his visit to Madison during our film festival last month gave me a chance to see some of it the way it should be seen: On a big screen, with superb projection and sound thanks to our new Kinotons. (Phil said his films had never looked or sounded better.)

Phil Solomon came of age in the late 1970s, after American experimentalists had already created several imposing masterpieces. Bruce Conner, Stan Brakhage, Hollis Frampton, Ken Jacobs (with whom Solomon studied in Binghamton), and many other filmmakers had in the 1960s and early 1970s given the world what Solomon calls Big Films. Collage-based (Conner’s A Movie and Report), lyrical (Brakhage’s Twenty-Third Psalm Branch), Structural (Frampton’s Zorns Lemma, Jacobs’ Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son), or narrative (Jim Benning’s 11 x 14), these monumental works were intimidating in their length, ambition, and formal and thematic sweep. What were young filmmakers to do?

Phil Solomon came of age in the late 1970s, after American experimentalists had already created several imposing masterpieces. Bruce Conner, Stan Brakhage, Hollis Frampton, Ken Jacobs (with whom Solomon studied in Binghamton), and many other filmmakers had in the 1960s and early 1970s given the world what Solomon calls Big Films. Collage-based (Conner’s A Movie and Report), lyrical (Brakhage’s Twenty-Third Psalm Branch), Structural (Frampton’s Zorns Lemma, Jacobs’ Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son), or narrative (Jim Benning’s 11 x 14), these monumental works were intimidating in their length, ambition, and formal and thematic sweep. What were young filmmakers to do?

Some of the juniors, Tom Gunning pointed out in an influential essay at the time, backed off from these epic visions. Aiming at a more intimate cinema, they used their forebears’ discoveries in modest, fairly impersonal ways–somewhat as Wallace Stevens’ chiseled compactness reworked the techniques that Eliot splashed on a bigger canvas in The Waste Land. Solomon agrees that he joined this deliberately “minor” filmmaking tradition, exploring the fine grain of imagery and what Gunning calls “submerged narratives.”

The task these young filmmakers set themselves was to present a recognizable world, and then poeticize it in a more modest way than the 1960s generation had. The tension between pictorial abstraction and realistic representation is central to much cinema, but it’s felt most keenly by experimentalists. Solomon pursued the problem through found footage and rephotography. Uncomfortable shooting original footage, particularly of people, he preferred to scavenge home movies and classic films to rework at his leisure. He filmed from television, old films, even Super-8 viewfinders. His optical printer stopped or stepped shots or blew up bits of the frame. He became identified with one particular technique: the use of chemicals to alter the film after it had been processed.

Solomon’s classics are unabashedly beautiful. The Secret Garden (1988) draws on children’s literature and film to present a dazzling image of paradise. James Cameron’s Avatar gives us glowing branches, but with the bland sheen of a Doré illustration. Who wouldn’t prefer Solomon’s radiant, evocative forest, created through optical printing distorted by lens aberrations?

Like Bruce Conner, Solomon enjoys popular media and its iconography, but unlike Conner’s his concern isn’t satiric or ironic. The Twilight Psalms are drawn from Twilight Zone and Outer Limits episodes, and images of Houdini flit in and out. The purpose is to enhance mystery and, inevitably, a sense of mournful decay.

The risk in such ravishing imagery is that it becomes merely pretty. Solomon doesn’t want to make decorative films, he says, and the pulsing, swarming shapes that gnaw into the figures recall the ravages of decomposing nitrate stock. Solomon says he practices “reverse archaeology”: “I throw dirt back on.” Dirt never looked better.

He’s reluctant to talk much about his methods, worrying that the conversation will turn away from the viewer’s experience. But he explained to us that once he has obtained his images, he “unmoors” them chemically by loosening the emulsion and subjecting it to chemical treatment. The result allows fungal growths and craquelure to overrun areas that harbor the silver bromide grains. Like embossing, the technique adds roundness and shading to the flat images. It reminds you that film has volume and that it can become, at very minute levels, a sculptural art.

Another risk of dazzling us with imagery is that the overall form of the film becomes elusive, merely a support for striking effects. One feature of both Structural Film and New Narrative was an insistence, in P. Adams Sitney’s phrase, on overall shape. Watching films like Zorns Lemma and J. J. Murphy’s Print Generation, the viewer is invited to work out a broad architecture into which each moment fits precisely. Solomon’s films are more diffuse, avoiding patterns that are perceptible on first acquaintance and moving toward more associative and elusive organization. What binds the films are recurring motifs (e.g., the hospital patients glimpsed in the punningly titled Remains to Be Seen) and emotional tone, often a quiet melancholy that builds toward lamentation.

I haven’t seen some of Solomon’s newest work, which reconfigures imagery from video games in the manner of machinima. Again, the samples on his site are very intriguing. But one screening at Madison brought us a very impressive recent item. At the end of the 2000s Solomon seems to have felt ready to tackle his own Big Film.

American Falls developed over several years, partly in reaction against the “one-liner art” Solomon saw as dominating the Whitney Biennial. American Falls began life as a gallery installation but in the 2010 version we showed in Madison, it was a triptych running nearly an hour. If The Secret Garden refers obliquely to children’s literature, here a national myth is boldly thrust forward. No “submerged” narrative here.

Referencing Ives’ “Three Places in New England” as well as Griffith, Keaton, Citizen Kane, Night of the Hunter, the Titanic, All Quiet on the Western Front, Pearl Harbor, the Rosenbergs, the JFK assassination, and the Civil Rights movement, American Falls offers nothing less than a panorama of twentieth-century American history. It starts with Annie Edson Taylor, who in 1901 became the first person to survive going over Niagara Falls.

The shots, bronzed throughout, seem stamped onto the surface of the screen, even as textures wriggle and pulse within the contours. I was reminded of a Rauschenberg combine, in which all manner of source imagery is given a busy but unifying finish. Another analogy is Gavin Bryars’ great musical piece The Sinking of the Titanic, which incorporates shards of spoken testimony into a ceaseless, majestically somber texture. (You can listen to some of it here.) Needless to say, Solomon references the Bryars piece too.

The film is a plangent survey of the failures of a dream: America has fallen. Yet even this “night prayer,” as Solomon calls it, can’t cancel the captivating charms of his pictures and sounds, and he knows it. When he was asked why Hitler didn’t appear in his saga, he replied that he didn’t want to make Hitler beautiful.

The sources for American Falls are listed extensively on Solomon’s site. (Another return to Big Art form, as with Eliot’s Waste Land footnotes?) In any case, on a single screening the film seemed to me to achieve a resonant eloquence. Big or small, a Solomon film merits seeing, hearing, and study. Although the films shine forth best on a big screen, Phil looks forward to making his work available to wider audiences on DVD. So do I. These are films you can live with a long time.

Tom Gunning’s essay mentioned above is “Towards a Minor Cinema: Fonoroff, Herwitz, Ahwesh, Lapore, Klahr and Solomon,” Motion Picture III, 1/2 (Winter 1989-90), 2-5. A detailed interview with Solomon appears in Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 5: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers (University of California Press, 2006), 199-227. Jacob W. at Making Light of It provides a very useful dossier on Solomon’s career, with some critical essays. Two strong essays on Solomon’s videogame-inspired films are Michael Sicinski, “Phil Solomon Visits San Andreas and Escapes, Not Unscathed: Notes on Two Recent Works,” Cinema Scope no. 30 (Spring 2007), 30-33, available here; and John P. Powers, “Darkness on the Edge of Town: Film Meets Digital in Phil Solomon’s In Memoriam (Mark LaPore),” October no. 137 (Summer 2011), 84-106.

Solomon’s vimeo page displays other aspects of his interests.

Special thanks to John Powers for programming these films and bringing Phil to Wisconsin.

P.S. 22 April 2019: Phil Solomon died on 20 April. This is a huge loss to American film. Because some of my links to his work online have failed, I’ve revised the references supplied at the start of this entry.

Crossroad (2005; Phil Solomon/ Mark LaPore).